CLASSROOM WORK DURING BLACK HISTORY MONTH

“We are each other’s harvest; we are each other’s business; we are each other’s magnitude and bond.”

— GWENDOLYN BROOKS, American Poet, Author, and Teacher

The story of Black History Month began its course in 1915, half a century after the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery in the United States, thanks to the Harvard-trained historian Carter G. Woodson’s determination to lead the study on black history. He announced a first History Week in February 1926. Black History Month began in 1970, and President Gerald Ford officially recognized it in 1976.

As an invitation to self-reflection, Michael Gonchar brought some important questions in a recent article in the New York Times:

What is your experience of learning about Black history in the United States? To what extent have you learned about the achievements of Black people in this country and the struggles they have faced, including slavery and Jim Crow? Do you feel that this is a topic that has been accurately and thoroughly taught in your schools? And what have you learned about the subject outside of the classroom?

The Waldorf classroom aims at praising cognitive, experiential and emotional learning embedded in the curriculum in a developmentally appropriate way. It is always an exercise in flexibility and introspection, embracing local culture while bringing universal values.

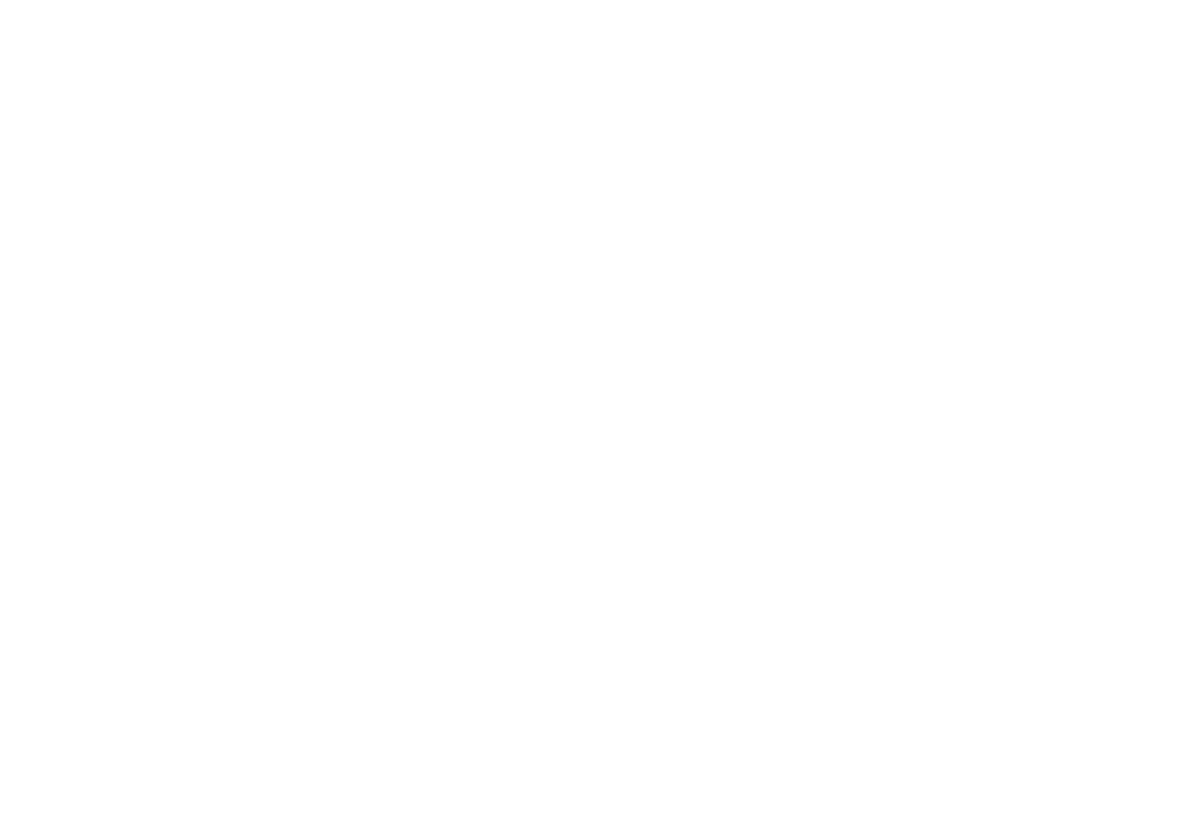

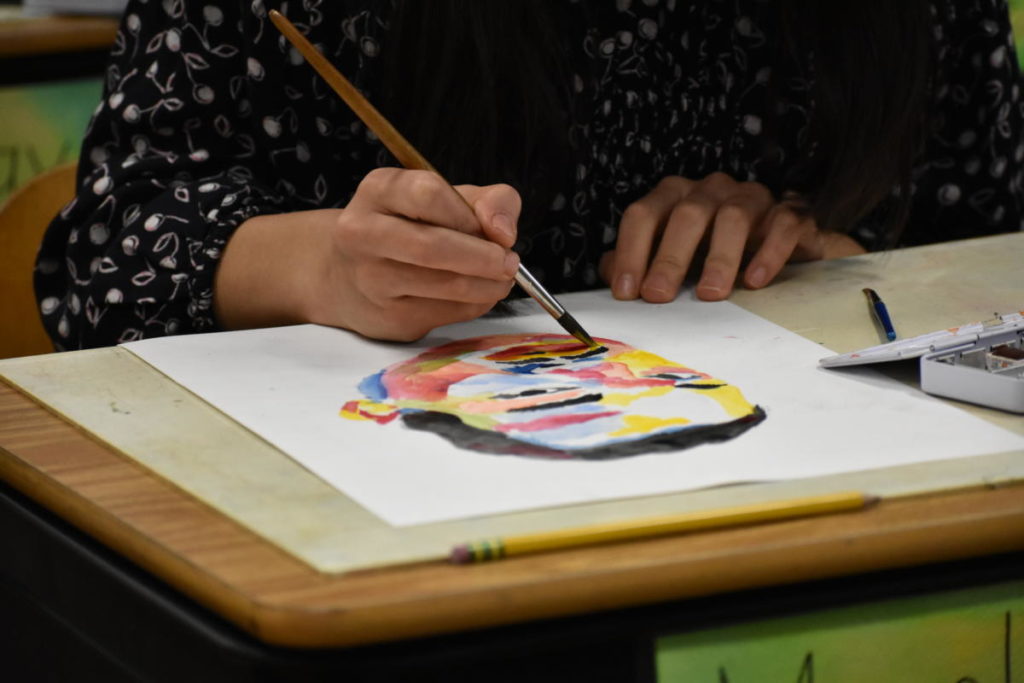

The early grades have been listening to stories about Ruby Bridges, Rosa Parks, Muhammad Ali, and others. The sixth-grade students have been working on a series of watercolor portraits during their painting class. The first two completed paintings in the series are of Martin Luther King Jr. and Brooklyn-born Shirley Chisholm, the first African American woman elected to the United States Congress. The artistic inspiration for the class was the, now iconic, portrait of MLK by Derek Russell.

In the Upper School, the seventh-grade students continue to learn history throughout biographies. Each student chooses one figure and studies their life and the events related to each one of them, followed by a drawing of their portrait. In seventh grade, students are guided in their growing ability to read critically. This is the age (12-14) of idealism, which means that learning from strong and inspiring figures will contribute to see history and the spirit of that age through the eyes of the protagonists, as well as contributing with the students physical and emotional development: “Our inner attitude or spirit changes the chemistry with which we are operating. In light of these findings, it might be easier to realize how important idealism (in the broad sense of the word) is to a developing teenager.”